Webコンテンツの表示

Webコンテンツの表示

The Vietnam War Comes to Marist: The 1966 Teach-In

A Personal-Historical Account

Charles F. Howlett, Marist '68

Professor Emeritus, Molloy College

Fifty-five years ago as the nation increasingly became embroiled in what many historians consider our most divisive and controversial war, a tiny college in Poughkeepsie took center stage. A number of notable political leaders and social justice activists traveled to Marist College and took part in a debate regarding the Vietnam War. Taking the lead in the Hudson Valley, and following on the heels of what had been occurring on many of the more prestigious universities in America, the college sponsored its own Teach-in. Capturing front-page coverage in the Poughkeepsie Journal the event certainly became newsworthy as college students and residents from throughout the region poured into the campus to be part of the first and only Teach-in of such national stature to take place in the Hudson Valley, let alone Dutchess County.

Vietnam and Beginnings of a War at Home

Clearly, it is generally understood that until the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars in the first two decades of the 21st Century, the 1960s conflict in Southeast Asia witnessed massive antiwar protests and considerable political upheaval. Failing to learn from the French colonial failure and in violation of the Geneva Accords, which had set elections for a unified Vietnam to take place in 1956, the United States agreed to support Ngo Dinh Diem when he proclaimed himself president of a newly-created Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) in 1955. By that time, peace groups in America had already been calling for a ceasefire in the war between Diem’s Republic of Vietnam and the communist-backed National Liberation Front since hostilities had broken out that very August. The U.S. continued its support of Diem’s repressive regime until it became so embarrassing that the American government acquiesced to his assassination in 1963, just weeks before President John F. Kennedy’s was killed in Dallas, Texas. In March 1964, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman J. William Fulbright, Democrat from Arkansas, and former Rhodes Scholar, called for a complete military disengagement from Vietnam. No response was forthcoming from Lyndon Johnson’s administration, which came into power after the Kennedy assassination. Then, some months later, the Gulf of Tonkin incident provided Johnson the necessary excuse for implementing military force. In August 1964, the U.S. claimed that two North Vietnamese gunboats had fired at an American naval ship off the coast of North Vietnam in the Gulf of Tonkin. Although there was some speculation about whether or not the ship had been fired upon (based on former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s The Fog of War, it is now widely accepted that there was no attack), it was enough for President Johnson to appear before Congress and request a formal resolution to commit military troops to Vietnam in the name of saving the South Vietnamese from communism.1

During the winter of 1964-65, the anti-war movement, countering the Johnson Administration’s charge of communist aggression, argued that the conflict was, in reality, a civil war not directed from Moscow or Beijing and that the U.S. had no right to be involved. According to various historians, the movement assumed three distinct parts as the war dragged on. First were the anti-imperialists who believed that the real enemy was America’s corporate ruling class; for these protestors, the war represented a revolutionary struggle for Vietnamese liberation against American imperialism. Second were the radical pacifists who saw the war as the real enemy, and advocated non-violent means to encourage immediate withdrawal of American troops. Last were the main-line peace liberals who emphasized the traditional means of political pressure to compel U.S. policymakers to negotiate an end to the war by providing for American withdrawal and a governmental role for the National Liberation Front in Saigon. Despite differences in substance and style, the most significant characteristic of the anti-war movement was its ability to coalesce and form new coalitions, which enabled the movement to sustain its momentum.2

Most notably, the protestors were also as heterogeneous as American society and not all would fit nicely into the three general categories mentioned above. Small town demonstrations were likely to include housewives, business people, doctors, dentists, ministers, and workers. Demonstrations in large cities added students, college professors, bohemians, clergy, teachers, veterans in uniforms, and show-business celebrities. Most importantly, at the movement’s grassroots, anti-war groups from pacifists to liberals viewed collaboration with American communists as far less heinous than the actions of their government and the indolence of the American people. Pacifists and political moderates saw the presence of radical activists or anarchists in their ranks as a tactical handicap but regarded the cause of ending the war as worth the association.3 Their sentiments were compellingly expressed by, perhaps, the nation’s most distinguished peace advocate, A.J. Muste, who commented sarcastically: “But ours is a society composed of people who somehow feel that…the deaths of hundreds, thousands, millions in war is…somehow moral, human, civilized…. Even more, this is a society in which people contemplate, for the most part calmly, the self-immolation of the whole of mankind in a nuclear holocaust.”4

Certainly, by the summer of 1965, leading Americans now were beginning to speak out against the war thus energizing the emerging student anti-war movement. I.F. Stone, the noted journalist, called for an immediate withdrawal. Senator Ernest Gruening (D- Alaska), Senator Wayne Morse (D-Oregon), both had voted against the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, political theorist Hans Morgenthau, George F. Kennan, father of the American containment policy, pediatrician Benjamin Spock, and retired Lt. General James Gavin either called for a ceasefire and negotiated settlement or urged the Johnson Administration to limit the U.S. military role in Vietnam and turn the war over to the Vietnamese.

Equally important, their respectable protest coincided with the anti-war “teach-ins” (informative programs held at universities throughout the country debating and questioning the merits of U.S. military involvement) that swept through the nation’s colleges and universities in 1965 and 1966. Having supported Johnson in 1964 as the “peace candidate,” many faculty members and students felt betrayed as he adopted the Vietnam policies of his opponent Barry Goldwater. On March 24th, an all-night teach-in at the University of Michigan attracted 3,000 participants. This event touched off a series of teach-ins across the country. “We are using our [U.S.] power to thwart and abort an indigenous social and political revolution,” charged Professor William Appleman Williams at the University of Wisconsin. Speaking at the University of Oregon, Senator Wayne Morse predicted: “Twelve months from tonight, there will be hundreds of thousands of American boys fighting in Southeast Asia—and tens of thousands of them will be coming home in coffins.” At the University of Michigan, Arthur Waskow of the Institute of Policy Studies—condemning militarism and conscription—cited Jefferson on slavery: “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just.” Artists, writers, and intellectuals were in the forefront of the protest.5

Historians certainly took note of these Teach-ins during the early stages of antiwar protests. And nowhere was this more evident than at a tiny college, situated on the banks of the Hudson River, just north of the city of Poughkeepsie, New York. According to authors Nancy Zaroulis and Gerald Sullivan in their study of the protests against the Vietnam War, “ teach-ins were held at institutions as different as Kent State and Berkeley, on campuses large and small, ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative,’ urban and rural: Chicago, Columbia, Pennsylvania, New York University, Wisconsin, Harvard, Goucher, Marist, Principia, Flint Junior College.” The purpose of these Teach-ins, the authors point out, “was to educate rather than to enlist recruits for protest against the Administration, but in the process of learning about what the United States was doing in Vietnam….”6

Marist in the 1960s

That was indeed the case in the spring of 1966, my sophomore year at Marist. Raised in a conservative, Catholic, household the 1950s had been marked by the rise of suburban America, the ideological struggle against Communism, and “duck and cover” as the threat of atomic and then nuclear annihilation hung over our heads. For the most part, the decade preceding the 1960s was highlighted by a conservative consumerism and political climate that witnessed conformity over disruption. Such would not be the case in the coming decade as the Vietnam War nearly tore apart the social fabric of the nation. I would be the first male in both my mother’s and father’s families to attend college.

In the early 1960s the college, founded by the Marist Brothers in 1929, resided on 125 acres on North Road (Route 9) along the banks of the Hudson River and the New York Central Railroad Line. The college existed in the shadows of important institutions such as Vassar College, International Business Machines, which would offer students internships to prepare them for the emerging world of computers, and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Estate and Presidential Library a few miles north of the campus. With the 1965 completion of a new 10-story building replete with living quarters for students, additional classrooms, meeting halls and galleries, bookstore, post office, ratskeller for social gatherings, and a large dining facility, the college now boasted three student dormitories, the circular building, Donnelly Hall, that was the primary meeting place for classroom instruction, the campus chapel, the Greystone Building where the Admissions Office was located as well as the President’s Office, and an old large garage converted into a gymnasium. On the north side of River Road, which led to the boathouse for the crew team, was a large outdoor pool used for holding clambakes in the warmer weather; nearby was the Novitiate for those students studying to become Marist brothers. The current football stadium was then home to the varsity soccer team, which I played for during my time as a student-athlete.

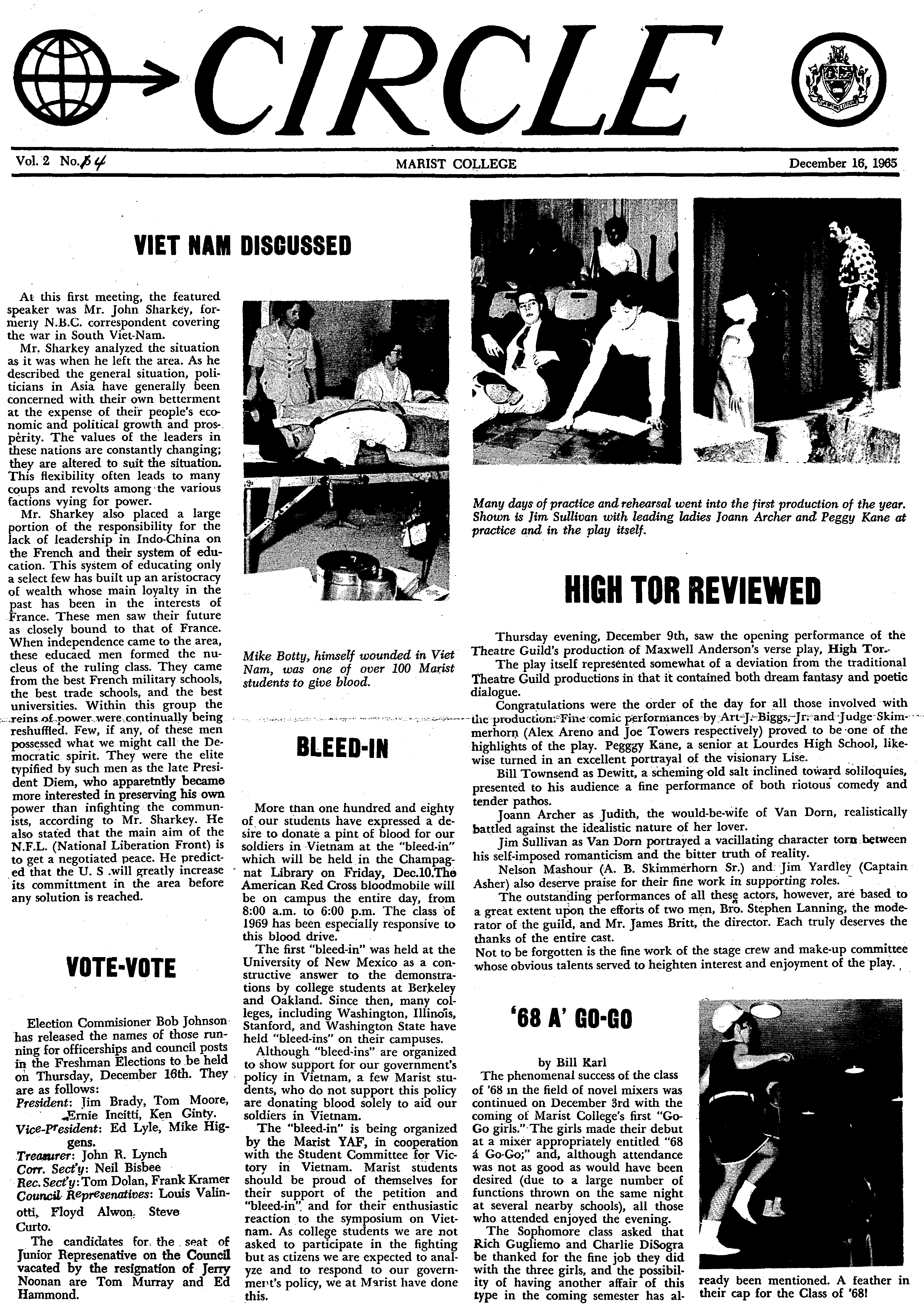

By the time I came to Marist in the fall of 1964, Vietnam was some far distant place on the other side of the world with little to no connection to my own personal life. But during my sophomore year, once American troops were being sent into combat and the rapid expansion of a military draft unfolded (the era of draft card burnings), Vietnam became a constant topic of conversation. The first real, public discussion about Vietnam occurred during the 1965 fall semester when NBC news correspondent John Sharkey, who recently returned from the war-torn region, came to campus, and presented his unflattering assessment of the situation. According to Sharkey, he placed a large part of the blame on the elites in South Vietnam who were unwilling to seek a negotiated peace with the National Liberation Front. He also predicted, correctly, that the United States would increase its military commitment long before a peace settlement would be reached.7

Organizing the Teach-in

Although college deferments were still in effect the real issue was how long this war would go on and what would happen upon graduation from college. Even though Marist would remain relatively quiet and not rocked by massive campus protests, there was a growing concern among the student body to learn more about why the United States was engaged militarily in Vietnam. At the time, little did we know that Marist would take center stage in the Hudson Valley when sponsoring its own Teach-in. The idea was hatched by George Gelfer, Class of 1967 and two of my classmates, Peter Petrocelli and George McKee. According to Gelfer, “We were silly enough to believe that our liberal arts college followed the ancient European model where different points of view were encouraged and freely discussed under the protective umbrella of ‘Academic Freedom.’”8

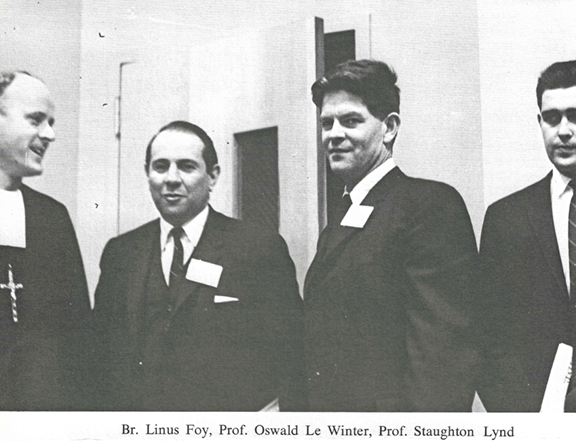

Uncertain about how the college administration would receive their request they took their case to Brother Linus Foy, college president. They were pleasantly surprised when Foy, sitting behind his desk in the Greystone Building, a campus landmark, granted them permission to formalize their plan. With no money and relying on the telephone and snail mail they began lining up an impressive number of speakers on both sides of the controversy. Faculty members also proved enthusiastic and gave steady advice to the three organizers, according to Gelfer. Among receptive faculty were Political Science Professor Louis Zuccarello, who arrived in the fall of 1965, Asian History professor Dr. Huan Chung Teng, Language Professor Pierre Belanger, and Academic Dean and Professor of History (my mentor), Dr. Edward Cashin. Serving as the moderator for the event was Bill Morrissey, who played an instrumental role as student coordinator.

When word got out that a Teach-in was about to happen at our college, I was, like many of my classmates, curious and happy that such attention would be brought to Marist. This was a big deal at the time since Marist did not have the name draw as its nearby college neighbors, Vassar and Bard. So many of us looked upon this as an opportunity to get Marist on the map. Quite naturally, college administrators were concerned about maintaining control and not having such an event put the college in a bad light. Their concerns were largely driven by an emerging radicalism among students on many college campuses as a counter-culture movement, which began sweeping the intellectual landscape; a movement that questioned the nation’s capitalistic underpinnings and a foreign policy aimed at stopping the spread of communism worldwide. However, they would not be disappointed.

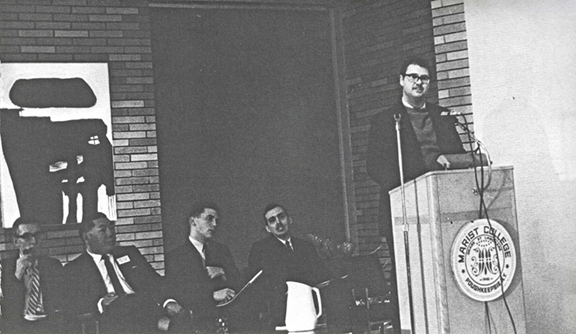

As it turned out, the speakers on both sides of the controversy presented their arguments in a reasoned and calculated approach. Allowed about twenty minutes, they read their prepared remarks and, to me, seemed fully engaged with their audience. There were no disruptions at all. It was a cordial and professional encounter. In keeping with the parameters structured for the event it was very educational and informative. It highlighted the justification and reasons why Teach-in were considered a respectable form of intellectual engagement. Questions from the audience were entertained after all the speakers had spoken.

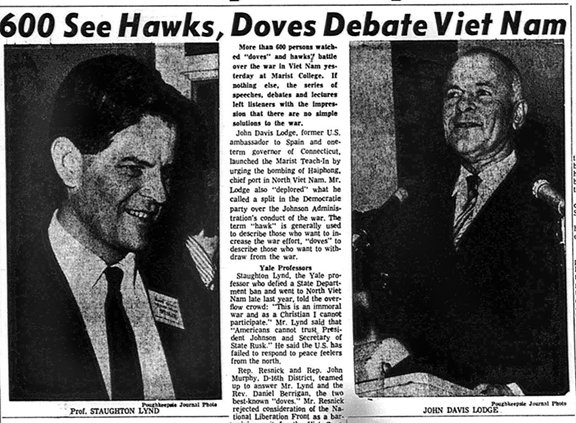

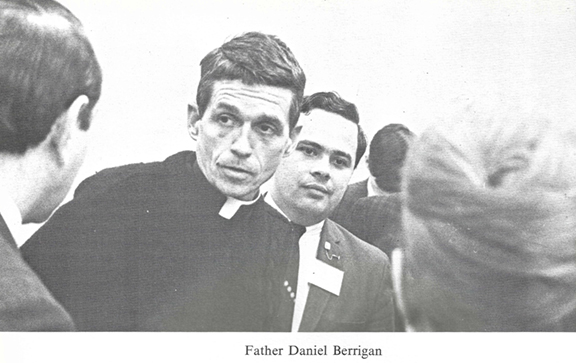

The list of invited speakers was impressive. Defending the U.S. position was one of the noted Chinese nationalist leader Chiang Kai-Shek’s generals and advisor to U.S. military groups in Vietnam, Gen. Bernard Yoh, Democratic Representative Joe Resnick of Ellenville, who two years later would lose in his bid for the U.S. Senate because of his position on the war, Democratic Representative from the 16th District covering the northern Bronx and the lower portion of Westchester County, John Murphy, author Christopher Emmet, a strong defender of a free Eastern Europe and World War II critic of Nazism and totalitarianism, free-lance correspondent Charles Wiley, who spent time in Vietnam, and John Davis Lodge, former ambassador to Spain, one-term governor of Connecticut, and brother of former Massachusetts Senator and ambassador to the United Nations, Henry Cabot Lodge. Critical of the war were the famous Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, who would later achieve national attention for burning files at the Catonsville Draft Board outside of Baltimore, Maryland, the noted Quaker and pacifist, Staughton Lynd, who would later be removed from his position as a history professor at Yale University for his criticisms of the war, the Reverend A.J. Muste, who many consider the most famous U.S. peace activist of the 20th century, New York City college professor Robert Dennis, and Derek Mills, a member of the peace organization Turn Toward Peace. Money was raised through funds allotted for college expenses hosting such events. Also helping to generate support and publicity for the event was the popular folk singer, Tom Paxton. As Gelfer noted: “[Paxton] agreed to play for us for just $200, which was probably barley enough to cover his expenses and a one-night stay at the Poughkeepsie Inn.” The day of the event the Poughkeepsie Journal added to the excitement with a brief font-page story, which read, “500 at Marist Hear Lodge.” Of course, the attendance would be much greater than originally expected.9

My Recollection

The Teach-in was held on a sunny and slightly warm late afternoon on March 22, 1966. The location was the spacious art gallery in the newly-constructed Champagnat Hall. As I approached the back entrance to the gallery and walked up the steps, a long line was already waiting to get in. But before they could enter to hear the speakers, each guest was met by members of the New York State Police and required to sign their name on a sheet. I suspected that this was for the purpose of keeping tabs on suspected radicals and members of the Students for a Democratic Society, which had been encouraging direct confrontation and militant protests against the war, attending the event. It did turn out that I was correct on that score.10

When I finally got in it was standing room only. All the seats were taken as students, faculty, and guests from neighboring colleges—Vassar, New Paltz, Bard, and Dutchess Community—and concerned residents from around the region packed the room. At the front of the gallery were seated the guess speakers and a podium to the side was set up allowing each speaker an opportunity to present their case. The event lasted well into the evening and was followed by a reception where the guest speakers intermingled with many who came to hear them speak.

What stood in my mind was how the critics of American military intervention presented their case passionately and eloquently, though adhering to the forum’s educational purpose. I remember Lynd arguing that the conflict was an extension of American imperialism evoking many of the issues raised by the late famous historian Charles Beard when insisting that the American revolution was conducted by elites for the benefit of their own vested interests while castigating the American administration leaders for failing to respond to overtures from peace leaders in North Vietnam. As a history major his argument struck me as original and historical in terms of the origins of America’s rise to world power. Appealing to the college’s own religious underpinnings, the Poughkeepsie Journal also quoted Lynd: “This is an immoral war and as a Christian I cannot participate.” Berrigan extended Lynd’s case by maintaining that the war was immoral and it was not so much a fight to contain Communism as it was to preserve America’s interests in the Far East and to uphold our commitment to France as a bulwark against the Iron Curtain in Europe.  What I was struck by was the measured tone presented by A.J. Muste, who was labeled by Time in 1939, as “America’s Number One Pacifist.” A leader in the American peace movement and one of the instrumental figures in the religious-pacifist organization with national headquarters in Nyack, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, he explained why “holy disobedience” was the necessary course of nonviolent action protestors should follow to pressure political leaders to make peace in Vietnam. Many in the audience applauded.11

What I was struck by was the measured tone presented by A.J. Muste, who was labeled by Time in 1939, as “America’s Number One Pacifist.” A leader in the American peace movement and one of the instrumental figures in the religious-pacifist organization with national headquarters in Nyack, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, he explained why “holy disobedience” was the necessary course of nonviolent action protestors should follow to pressure political leaders to make peace in Vietnam. Many in the audience applauded.11

On the other side, both the Chinese general, Yoh, and Lodge insisted that America’s presence was needed to preserve the democratic government in South Vietnam and to check the growing influence of Communism in Asia—already firmly established in China. Lodge was actually the first speaker and insisted that the bombing of Haiphong (North Vietnam) would end the war quickly. Congressman Resnick maintained that the National Liberation Front was taking its marching orders from Peking (Beijing) and the end game was “a Red Chinese plan for control of Asia.” Murphy sought to assure his audience that any direct confrontation between the U.S. and China was not going to happen since Chinese military divisions would be unable to drive into Vietnam “with the same speed they demonstrated in entering North Korea during that war.” More measured in tone their position reflected the theory of containment and of peace through force; they cautioned their listeners not to return to a post-World War I pattern of isolationist pacifism but to meet the threat head-on in this diplomatic Cold War period challenging American hegemony.12

The audience, of course, was polite and respectful though it was clear to me that not everyone was satisfied based on what was presented from those defending the war. More seemed skeptical as to the reasons and justifications supporting U.S. military involvement. That may have been attributed to the growing skepticism on the part of students in attendance as more and more in the media began challenging the war effort and an increasing opposition to the military draft. What was obvious, nonetheless, was that the entire event ran smoothly and both sides were able to offer their findings without any heated exchanges. It turned out to be, as advertised, an educational awakening and one that remains imbedded in my collective memory.

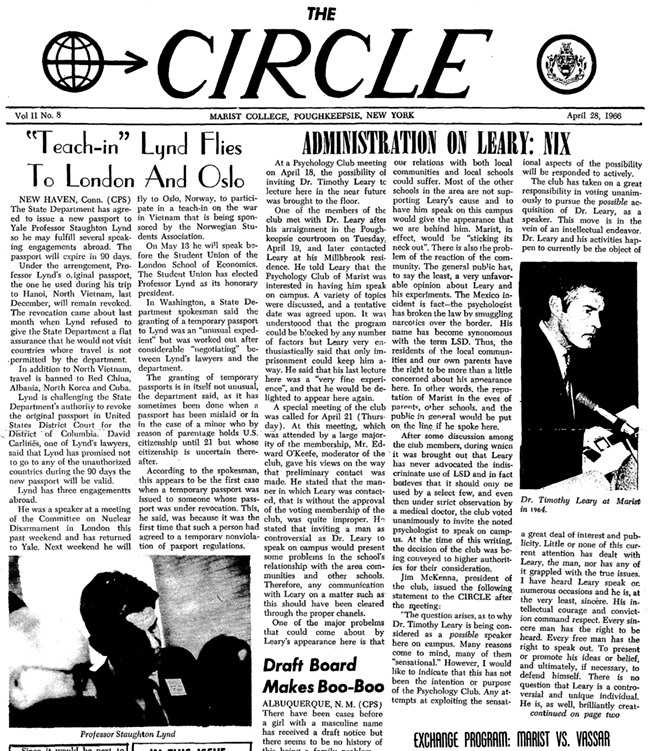

In late April the student newspaper, The Circle, continued following events surrounding Lynd’s activities after the Teach-in . Lynd had been one of the headliners at the event, so it was only appropriate that space be devoted to his subsequent antiwar activities. By this point in time he had become one of the leading, outspoken academic critics of the war. More importantly, his actions coincided with the growing antiwar feelings spreading throughout most college campuses across the nation. What the student newspaper covered was the State Department’s reissuing of Lynd’s passport so that he could fulfill three speaking engagements overseas. What led to the revocation of his passport was a trip he made to Hanoi the previous December, three months prior to his appearance at the Marist College Teach-in.13

Subsequent Antiwar Events on other Campuses

The national event at Marist also inspired a more local event at Vassar two months later. In May, a “Viet Teach-In” was moderated by Vassar history professor Charles Griffin. It was open to Vassar students and Dutchess County residents. Although it did not attract national speakers, the gathering did promote further discussion about whether or not the United States should continue expanding its military presence in Vietnam. The teach-in “featured topical speeches on Vietnam given by Vassar professors and a host of guests from institutions including Columbia, Sarah Lawrence, Bryn Mawr, and the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute.”14 The momentum for offering educational forums discussing the Vietnam War began to take hold in the Hudson Valley as the region’s residents and college students were more open to listening to both critics and supporters.

During the Vietnam War years and after the Marist Teach-in provided greater latitude and exposure to those in disagreement with the war’s conduct, the Hudson Valley would experience numerous antiwar proclamations and protests on other college campuses. At Bard, for example, the student newspaper, Bard Observer, reported in December 1967, that the Beekman Arms Hotel in Rhinebeck granted permission to put on a production this coming March of the “Revolutionary Affair,” an antiwar play produced at the college by the New Action Committee. More dramatically, in unison with student sentiment, Bard’s faculty Committee against the War proposed its own "tax withholding protest" stating that “the costs in blood and goods, in world condemnation and domestic regression, and in moral shame, are now out of all proportion to any national gain.” “Never before,” the statement continued, “has the Bard faculty organized to speak out together on a national problem…We teach boys who are being asked to fight in Vietnam. We stand for the community of culture and intellectual and conscience….”15

Furthermore, that same year a Stop the Draft Week protest against Marine recruiters was the occasion for the first recorded demonstration at Dutchess Community College, in New York’s Hudson Valley. By 1968, antimilitary protests had become far more common in the Hudson Valley. At nearby State University College at New Paltz, in Spring 1968, officers assigned to the New York State Police “Red Squad” closely monitored the formation of an Ad Hoc Committee on Military Recruiting. Co-sponsored by the campus chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (a radical student organization first established in 1962 and led by antiwar leader, Tom Hayden) and a community peace group, the committee’s manifesto made clear what was at stake:

The Marines, the shock troops of American foreign policy, are engaged in the subjugation of Vietnam, and recruiting is essential to that operation. This is the context in which the problem of military recruiting on campus must be discussed … There is a war on; something must be done.16

And in 1969, as public opinion against the war continued to grow, Vassar College established its own ad hoc Committee to End the War in Vietnam as well as a “spontaneous publication,” called Blood and Fire, “publicizing campus anti-war seminars, vigils, marches, and protests.”17

Although Marist did not experience any on-campus student antiwar demonstrations while I was there, it did take center stage for sponsoring a Teach-in during the early stages of the Vietnam conflict. In fact, Marist was the only college in the Hudson Valley to sponsor such a national event about the conflict, one that was a significant expression of the growing concern over America’s military commitment in Vietnam. Sympathetic faculty and administration were willing to introduce the Marist community to the growing controversy surrounding this war. It did so at a time when not quite one-quarter of U.S. college students favored negotiation or withdrawal in Vietnam. That would change, however, by the time I graduated in 1968 and eventually served in the military during that conflict, which, at that time in our history, had been “America’s Longest War.”

All images appear here courtesy of the author and the Marist Archives and Special Collections.

End Notes

1. William J. Fulbright, The Arrogance of Power (New York: Vintage Books, 1966); Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York: Viking Press, 1983), Chapter. 2; George C. Herring, America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975 (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc, 1996), passim.

2. Joseph R. Conlin, American Anti-War Movements (Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publishers, 1968) passim. See also, Charles DeBenedetti, The Peace Reform in American History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), Chapt. 8. See also, Tom Wells, The War Within: America’s Battle over Vietnam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 28-38; Mel Small, Johnson, Nixon, and the Doves (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988), 78-84, passim; and DeBenedetti with the assistance of Charles Chatfield, An American Ordeal: The Antiwar Movement of the Vietnam Era (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990), 387-408.

3. Conlin, American Anti-War Movements, 18-24.

4. Quoted in Jo Ann Robinson, Abraham Went Out: A Biography of A.J. Muste (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981), 202. See also, George F. Kennan, American Diplomacy, 1900-1950 (NY: Mentor Books, 1962). See also, Lawrence S. Wittner, Cold War America (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974), passim.

5. Patti McGill Peterson, "Student Organizations and the Movement in America, 1900-1960" in Charles Chatfield, ed., Peace Movements in America (New York: Schocken Books, 1973), 116-32; Kenneth J. Heineman, Campus Wars: The Peace Movement at American State Universities in the Vietnam Era (New York: New York University Press, 1993); Marc Jason Gilbert ed., The Vietnam War on Campus: Other Voices, More Distant Drums (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2001). James Eichsteadt, “Shut It Down,” New York Archives 7 (Fall 2007), 8-12; Robbie Lieberman, “’We Closed Down the Damn School’: The Party Culture and Student Protest at Southern Illinois University during the Vietnam War Era,” Peace & Change 26 (July 2001), 316-331; Louis Menashe and Ronald Radosh, eds., Teach-ins: USA (New York: Praeger, 1967), passim.

6. Nancy Zaroulis and Gerald Sullivan, Who Spoke Up? American Protest Against the War in Vietnam, 1963-1975 (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1984), 37.

7. “Vietnam Discussed,” The Circle Vol. 2, No. 4 (December 16, 1965), 1.

8. Personal Reminiscence by George Gelfer, August 23, 2017. His personal reflections were written as part of his 50th Class Reunion in 2017, and shared with this author.

9. Ibid. See also, “500 at Marist Hear Lodge,” and “600 See Hawks, Doves Debate Vietnam,” Poughkeepsie Journal (March22, 23, 1966), 1 & 1-2. I wish to thank my classmate, Joe Brosnan, Marist '68, for alerting me to Congressman Joe Resnick's participation at the Teach-in.

10. Student activism related to antiwar protests in the Hudson Valley are recorded in surveillance reports and other materials in the New York State Police Bureau of Criminal Investigation Reports, Non-Criminal Investigation Files, New York State Troopers Files, New York State Archives, Albany, New York.

11. “600 See Hawks, Doves Debate Vietnam,” 1; my recollection of Muste’s appearance is recounted in my book, Troubled Philosopher: John Dewey and the Struggle for World Peace (Port Washington, NY; Kennikat Press, 1977). As I wrote: “This book has its genesis in the spring of 1966, when as a sophomore in college, I had the unique opportunity of listening to A.J. Muste, Staughton Lynd, and others speak out against the Vietnam War during one of the many teach-ins taking place on college campuses throughout the nation.” See also, Charles F. Howlett, “A.J. Muste: Portrait of a Twentieth-Century Pacifist.” In Donald W. Whisenhunt, ed., The Human Tradition in America Between the Wars, 1920-1945 (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 2002), 1-20. Muste was 82 years-old at the time and would pass away in less than a year.

12. “600 See Hawks, Doves Debate Vietnam,” 1. For a short but interesting discussion on this score consult, Charles F. Howlett, “Forgotten Fellow Travelers in the Struggle Against War,” Reviews in American History Vol. 28, No. 4 (December 2000), 615-624.

13. “’Teach-In’ Lynd Flies to London and Oslo,” The Circle Vol. II, No. 8, (April 28, 1966), 1.

14. Kirk, Charlotte. “Faculty to Decide on Topics For Viet Teach-In Participation,” The Vassar Miscellany News, 27 Apr. 1966. The moderator, the distinguished Latin American history professor, and Dean of Faculty Charles C. Griffin, retired that academic year from Vassar. In the fall of 1967, he then served as a visiting professor at Marist. I became one of his students. Both he and Dr. Cashin influenced my future career in the field of history and education. For more information about Vassar’s views and opposition to the war, consult the Vassar Encyclopedia, historian’s office, Vassar College.

15. “Faculty Anti-War Consider Tax Protest,” Bard Observer, Vol X, no. 11 (December 19, 1967), 1,3; https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/observer/.

16. This information is based on a forthcoming work by Seth Kershner, Scott Harding, and Charles F. Howlett, Breaking the War Habit: The Debate over Militarism in American Education (University of Georgia Press).

17. Vassar in Wartime, http://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/.